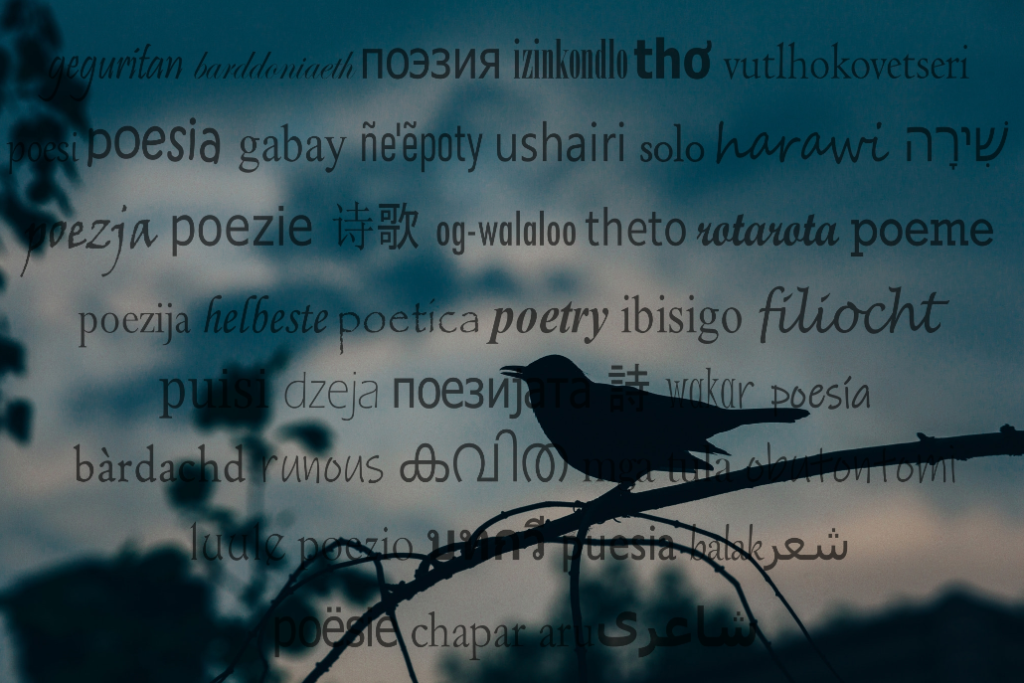

Stories are how we share who we are, what the world is (and has been) like, and the preciousness we seek to sustain. Poetry crystallizes stories and burns them to their essence through taste, sound, texture, and imagery that is, at times, sharp and other times is soft and nuanced. Less is more. Below are three nature poetry anthologies that include plenty of bird poems and appearances, and also broaden the scope to other sentient beings and the larger natural world.

Black Nature: Four Centuries of African American Nature Poetry, Camille Dungy, ed.

“why / is there under that poem always / another poem?” poet Lucille Clifton poses at the beginning of Black Nature. What is underneath many of the nearly 200 poems in this 2009 anthology are experiences in nature of black and brown poets, and how different – and often perilous – from many of the benign outings resulting in pastoral poems those of us with skin privilege have. This volume includes many of the most luminescent poets shining light on the experiences of African Americans urban and rural from the early years of enslavement to an intimate relationship with the land from working the fields, to the solace of nature, the horrors of nature as a tool of violence, the civil rights movement, advances, and backlashes.

Poets include Phillis Wheatley who, in 1773, became the first black person to publish a book of poetry in the Colonies, U.S poets laureate Robert Hayden, Rita Dove and Natasha Trethewey, as well as other notables – Langston Hughes, Cornelius Eady, Toi Derricotte, Gwendolyn Brooks, Major Jackson, Yusef Komunyakaa, Audre Lorde, Alice Walker and Richard Wright.

Poem titles which suggest the poem underneath the poem include “a brown girl’s nature poem: provincetown”, “We Are Not Strangers Here”, “At 57, My Father Learns to Grow Things”, and “Boll Weevils, Coyotes, and The Color of Nuisance”.

Of course, birds figure prominently in the anthology – California Condor, blackbird, peacock, hummingbird – as symbols of flight and freedom, awe and resistance, resilience and mortality. So, too, do yellow jackets, skunks, ants, rats and other animals, trees and plants. In “The Bees” by Audre Lorde, young boys try to stone a flock of bees while their female classmates find beauty in the insects. “Hey, the bees weren’t making any trouble!” / and she steps across the feebly buzzing ruins / to peer us at the empty, grated nook / “We could have studied honey-making!”

The story of the United States for too long has been told as a monolith through white writers writing in prose. Black Nature shifts the lens to a greater inclusiveness by not only who is telling the story – and stories – but how.

Cascadia Field Guide: Art | Ecology | Poetry, Elizabeth Bradfield, CMarie Fuhrman, Derek Sheffield, eds.

Field guides commonly appeal to readers through written descriptions and illustrations of flora and fauna. This 2023 field guide has a twist – each of the 126 entries is accompanied by a poem. Stretching from northern California to southeast Alaska, and east to the Sawtooth and Bitterroot mountains of Idaho, Cascadia in this field guide also includes British Columbia and a touch of Yukon Territory, with elevations ranging from sea level to Mount Rainier’s 14,410 feet.

Those of us who live west of the Cascade mountains may be familiar with many of the entries – Pacific Wren and madrona, red alder and salmonberry, moon jelly, salal and banana slug. Less familiar are the sentient beings on the dry side of the Cascades. So, on a recent trip to eastern Oregon’s Wallowa mountains and high desert, I read sections on shrub-steppe, eastern rivers and pine forest. There the American Dipper, black cottonwood, Chukar, ponderosa pine and giant Palouse earthworm are regaled.

The field guide, organized around 13 bioregions, also includes coastal and high mountain species – glacier lily, beargrass, hoary marmot, Clark’s Nutcracker, giant Pacific octopus, sea otter and Tufted Puffin, to name a few.

The field guide is rich with poetry and visual art from a wide variety of Northwest indigenous and non-indigenous contributors. Contributors include Olympia poets Lucia Perillo and Bill Yake, former Washington state poets laureate Rena Priest (Lummi), Claudia Castro Luna, Kathleen Flenniken and Elizabeth Austen, former Oregon poets laureate the father-son duo William Stafford and Kim Stafford, science fiction writer and poet Ursula K. Le Guin, and Denise Levertov, founder of Writers and Artists Protest against the War in Vietnam.

Using three literary and artistic mediums – poetry, prose, and visual art – Cascadia Field Guide reaches a broader audience than had the anthology used only two of those forms. As Gary Snyder wrote in “Little Songs for Gaia” about one of my favorite birds – the Dipper, or Ouzel:

trout-of-the-air, ouzel,

bouncing, dipping, on a round rock

round as the hump of snow-on-grass beside it

between the icy banks, the running stream

right in!

you fly

Here: Poems for the Planet, Elizabeth J. Coleman, ed.

“A book is a burning, smoking piece of conscience”, Boris Pasternak wrote. And this anthology of 128 poems by a diverse group of contemporary poets from around the world certainly is. They make the case for climate action in this 2019 anthology that is mostly poetry, and bookended with a foreword by His Holiness the Dalai Lama and a concluding guide to action by the Union of Concerned Scientists.

A role of a poet is to bear witness. Many of the poems in Here do that through poem stories of the animals and plants of today, to create a record of what will diminish or disappear altogether – a memory of flocks of birds that filled the sky, and salmon that blanketed rivers and streams. These poems show us the abundant – and diminishing – natural world in hopes that we will work to protect and preserve it.

From preciousness to peril to hope, poems in this volume are grouped thematically: “Where You’d Want to Come From: Poems for Our Planet”, “The Gentle Light that Vanishes: Our Endangered World”, “As If They’d Never Been: Poems for Animals”, “Like You Are New to the World: From Inspiration to Action”. Some of the freshest and most moving poems were written by poets between the ages of six and 18 and grouped within the theme “The Ocean Within Them: Voices of Young People”.

A favorite poem is “How to Be a Hawk” by 11-year-old Griffon Bannon, a visual and visceral piece of flapping wings, scooping up a mouse, bringing down an old vulture. “…Soar across the land feeling / proud of your hawk’s sight. // Rule the air.”

A goal of this anthology is to “galvanize readers to address the environmental crisis head one, with enthusiasm and without the paralyzing fear that leads to indifference and inaction”, wrote Elizabeth Coleman, editor of Here: Poems for the Planet. “We want to encourage a sense of urgency and hope…to reach those already engaged, and those sitting on the sidelines in a new way”.

–Suzanne Simons

Photo credit: Poetry in Many Languages, compiled by Rachel Hudson.