By Anne Kilgannon

My first thought is, I want to meet Noah’s mother! Really, both his parents. When he was still in high school he relates that he was inspired by a nature show on TV narrated by David Attenborough to study vultures. (Can’t you just hear that wondrous whispering voice!) As a first bird-of-interest….an interesting choice! The question he was inspired to investigate was, did vultures hunt by sight or smell? And as Noah conceived it, all he needed was a dead deer carcass to attract his subject and further, now that he had achieved a driver’s license, all he had to do was comb the back roads of his neighborhood to locate a fresh one. As he tells this story and how it played out with such wry humor and oh-gosh enthusiasm, the reader of The Thing With Feathers can’t argue with his plan. At least we don’t have to smell it, though, as we wait patiently with him in his backyard for some vultures to show up. His parents agreed that hands-on science experience is essential, albeit with pinched noses perhaps, and have supported and cheered their extraordinary son through such a variety of bird-centric experiments and globe-trotting that he is now a world-renowned expert in that rarefied field of study. And he has never lost his initial sense of amazement and wonder.

With study and dedication, Strycker has only deepened his engagement with the bird world since that early foray. His collection of essays, featured in “Feathers,” is well grounded in the latest research and appreciation of the work of others while still delivered in Strycker’s signature style. Readers are regaled with his early—and earnest—work on vultures, but he is equally fascinated by the science of how starlings flock and wheel in unison without crashing into each other, and how hummingbirds burn through life at high speed, while pigeons are smarter than usually credited. He examines the concept of irruptions with a focus on snowy owls and studies the role of fear in penguins while bouncing off insights developed by Darwin. Strycker is full of cogent reflections on the issues still being explored around the workings of evolution, the role of habitat, and the place of humans in nature. He’s interested in everything and how it all fits together. Really, anything to do with birds attracts his respectful attention and thoughtful analysis: dancing parrots, the pecking order among domestic chickens, albatross marital relations, and the sex lives of other birds, too. Strycker doesn’t just skim the surface of all these topics; he has clearly read deeply into the relevant literature. He also has such wide and varied personal experiences with birds of all kinds that his comments are a real addition to the works he has studied.

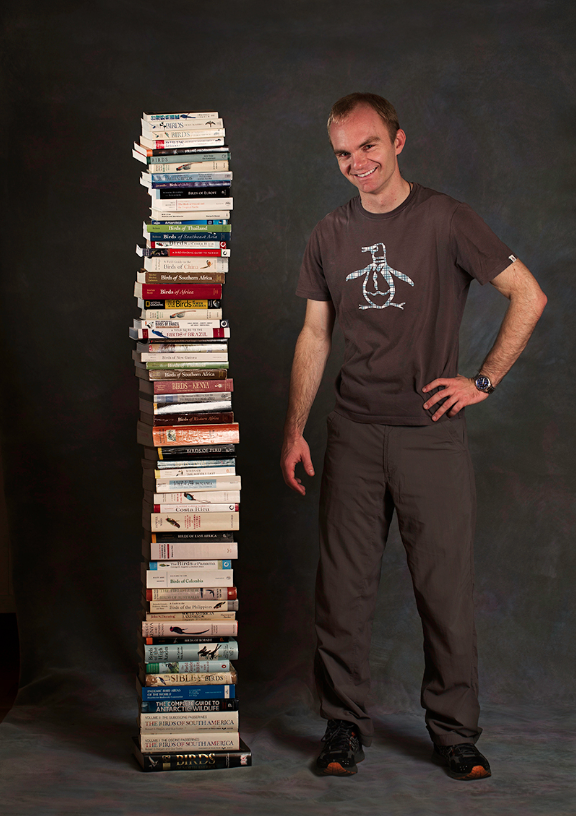

That broad experience—his bona fides—is on even fuller view in another book, Birding Without Borders, published in 2017 just three years after “Feathers.” I note those dates with some awe; the pace and intensity of his work are breathtaking. This book is the story of his record-breaking Big Year, not of one country or continent, but of the world. It’s nothing short of astounding, and not just because he does set a new record of birds seen and documented. He includes a photo of himself with an enormous stack of bird guides for all the countries on his itinerary, I think not to impress, but just to note how much there is to see. Although he carried his electronic files made from these guides, he appears to have committed the field marks, calls, habitats, and other details concerning hundreds of birds to memory. He’s not just listing birds as he goes, he knows those birds and how to find them, what they eat, how they court and nest, migrate, and fit into world evolutionary trends. His knowledge is dazzling but understated; he writes about his incredible experiences but keeps the focus on the birds, their beauty, grace, and allure.

The other focus Strycker keeps is the relationships he develops with local birders in each country he visits. This part of his story is at least as important and significant as the record number of birds he scrupulously records. Again and again, he gives credit to these birders who know their fields and forests best for their guidance and ingenuity that helped him achieve his list. We get to know them as individuals, as fellow birders, and enthusiasts playing a role in counting and caring for birds locally and globally. It is so heartening to learn more about the more and more linked chain of birders worldwide who document local species—species we may “share” as birds migrate their distances—and work for their conservation. We can all become partners in this era of communication and the global-wide crisis of climate change. Strycker, through his personal adventures and relationships, is helping knit together a community of care for birds that stretches from South America to the Middle East, several African nations, India, Southeast Asia, China, Indonesia and the Philippines, Papua New Guinea, Australia, and beyond. (A list of countries and species is appended that is a crash course in world bird identification for those ambitious enough.)

Both books are grounded in serious science and a deep sense of responsibility and environmental ethics. But they are far from somber! Strycker has so much fun even when he is dead tired from travel, stranded with car breakdowns and other mishaps, and straining to make a deadline. He’s always up to see another bird, to admire and marvel, experience and learn firsthand each and every species. There is no substitute for seeing a bird in its habitat with your own eyes. Reading Strycker is, however, a pretty good close second for those us unlikely to wade through swamps, climb mountains or drag a dead deer into our back gardens to witness what happens next.

Photo credit: Noah Strycker by Bob Keefer.