By Kim Adelson

This article is the second installment of my summary of the changes in winter bird populations found in and around Olympia, as determined by our annual Christmas Bird Count. As before, my analysis begins with data collected in 1978, since it was at that time that our local Count began to draw large numbers of participants. The focus this time is on diurnal raptors.

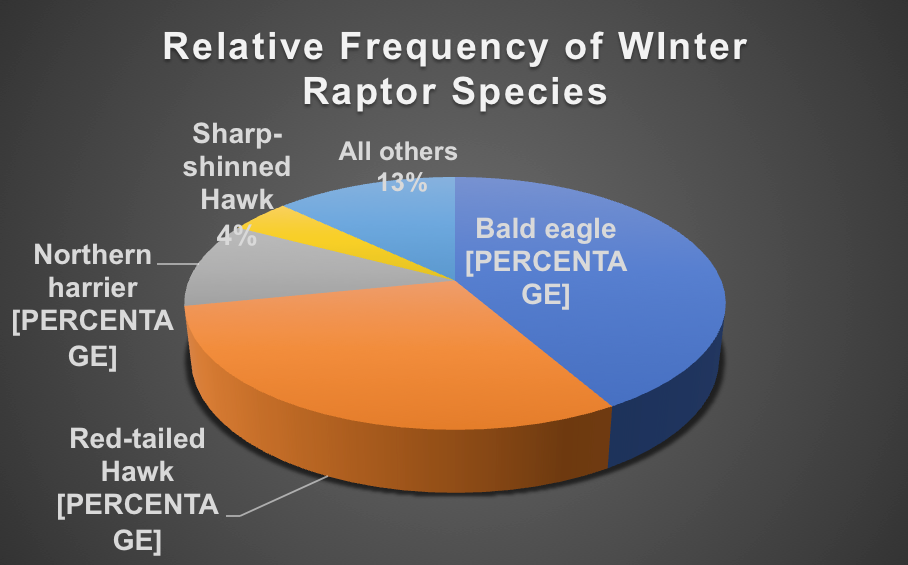

“Diurnal raptor” refers to birds from two separate taxonomic orders that are actually not closely related to each other: the Falconiformes (falcons) and the Accipitriformes (which includes buteos, eagles, New World vultures, as well as accipiters). While the Falconiforms are most closely related to parrots and songbirds, Accipitriforms are kin to owls and woodpeckers. The fact that they look and behave so much alike is due to convergent evolution – in other words, the parallel pressures they faced to survive caused them to become similar in form. In particular, both types of birds take down their prey by using their talons rather than their hooked beaks. These birds make up about 4% of all the birds seen in the Christmas Bird Count. Sixteen species of diurnal raptors) have been observed at least once by our counters. Six of those — Turkey Vultures, White-tailed Kites, Northern Goshawk, Red-shouldered Hawk, Gyrfalcons, and Prairie Falcons – have been seen only one or several times over the past 39 years. This isn’t surprising, since we don’t generally view these birds as belonging here in the winter (or at all). As shown below, four species make up the bulk of the nearly 6000 raptor observations made during the Count:

Although the exact percentages change, these same four species have been the ones most commonly seen since 2000 as well during the entire 39-year period. In the 1970s and 1980s, the profile was different. (More on that later.)

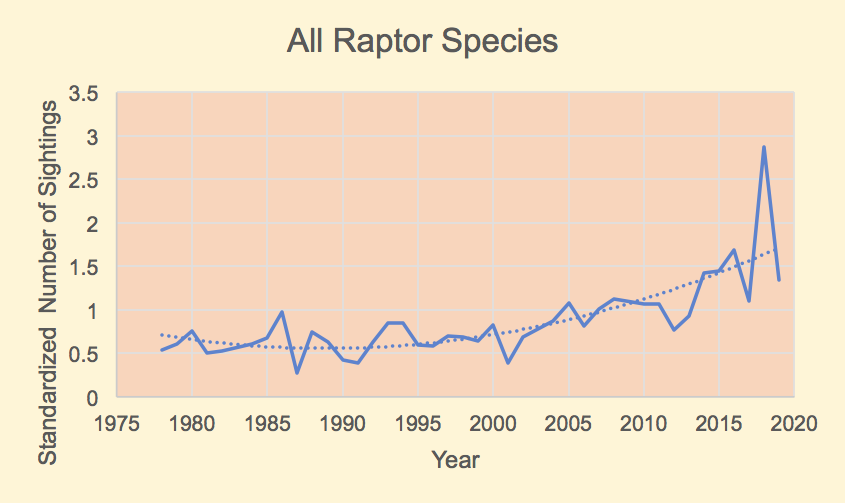

Overall, an increasing the number of winter raptors has been counted, especially since 2000. Good news! (All assertions about time trends are based upon the regression analyses that I ran; I will not bore you with the R and p values.)

Note: the numbers on the Y axis (up the left side) of this and all following graphs reflect the adjusted number of birds seen on the Bird Count. The raw numbers of observed birds are standardized by the numbers of groups that were out observing and the number of hours they spent looking. For example, if 5 groups were out for 10 hours each, that is fifty “group hours”. Say that they collectively saw 100 doves/pigeons in that time: 100/50= 2 standardized group hours. This converted statistic is a more accurate reflection of bird density than total number of birds counted due to yearly differences in the number of count participants.

Not all species, of course, contribute to this increase. Three, in fact, have been seen less frequently in recent years.

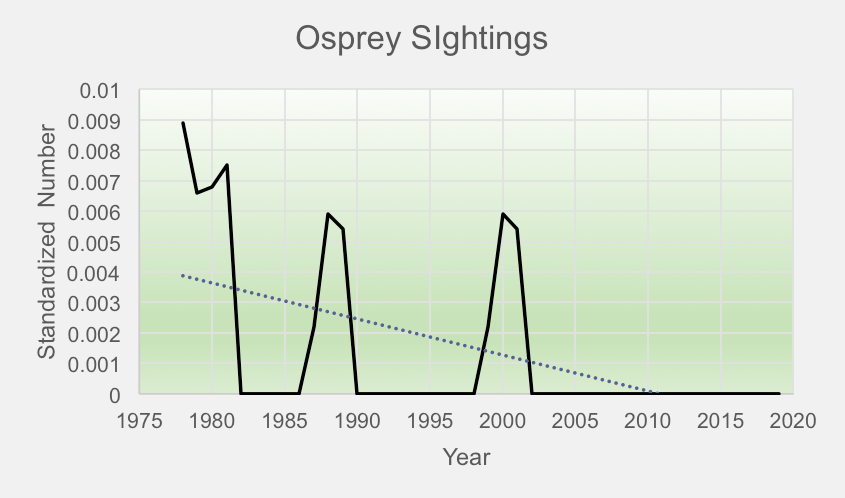

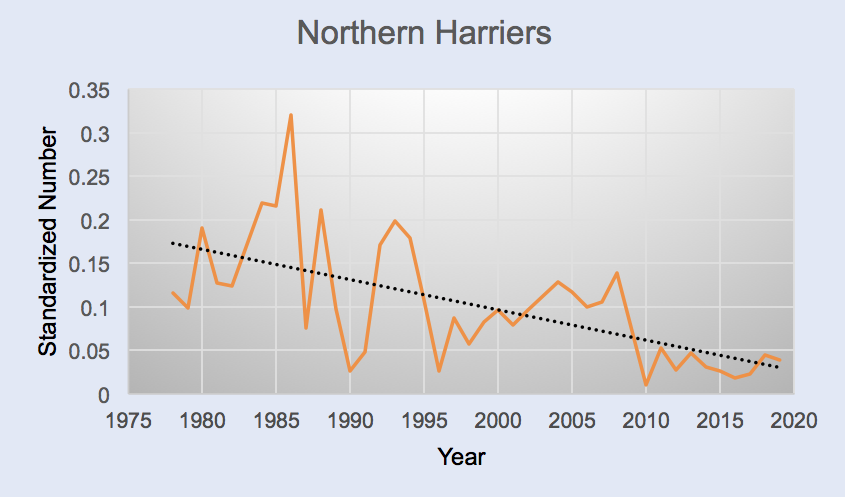

Species Whose Numbers are Decreasing: Three types of raptors are in decline in the winter in our area.: Ospreys, Rough-legged Hawks, and Northern Harriers. Ospreys have not commonly been seen here in the winter at any point during the 39-study timeframe; no more than one was ever seen in any given year. Our last Bird Count Osprey was observed in 2001; there have been none during the past 18 years.

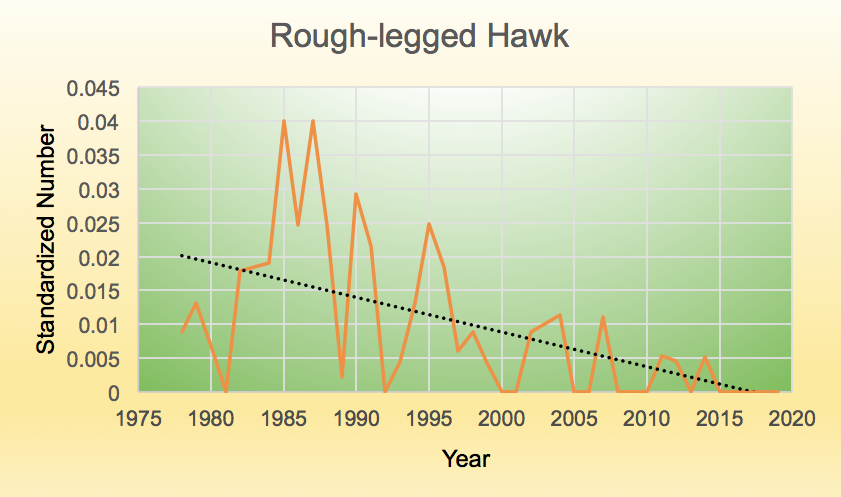

Although Rough-legged Hawks are in and around Olympia – and as many as 5 have been seen during any given Count — we are at the very Western edge of their winter range and they make up less than 1% of our raptor sightings.

Fortunately, they are not endangered overall, even though we are seeing fewer and fewer of them.

As noted above, Northern Harriers are the third most commonly observed raptor observed here in the winter. As many as 35 have been seen in a single count, although the average has been closer to 17. In the past decade, in contrast, the highest number observed was 10 and the average was 6. The decline is easily observed in the following graph.

Regrettably, their population has been dropping throughout the U.S., not just here in the South Sound.

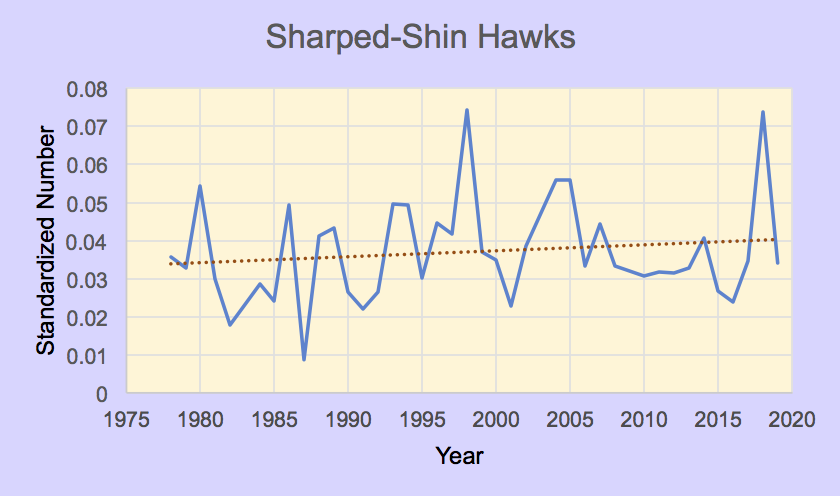

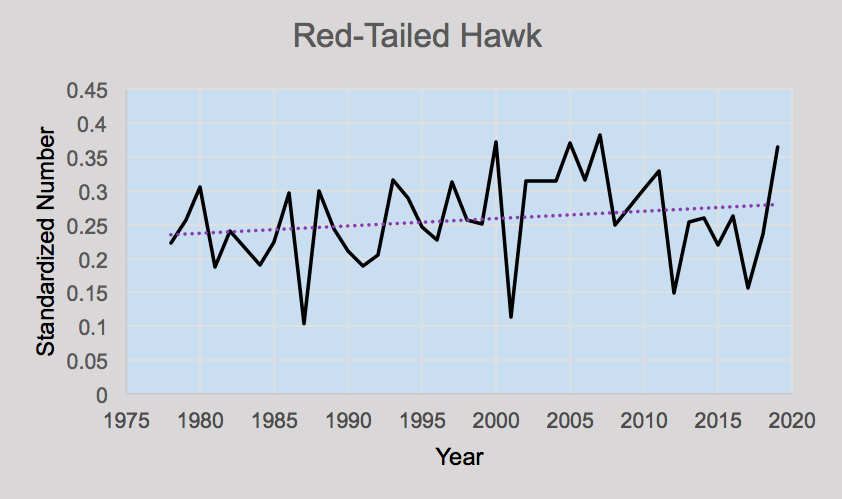

Species Whose Numbers Have Been Holding Steady: Only two of our raptors have been seen in consistent numbers for the past four decades: Sharp-shinned Hawks and Red-tailed Hawks. Although the trendlines appear to slightly increase, the rises are not statistically significant.

Since these two species are among our most common winter raptors, their continued thriving in Thurston County has a great impact on the overall health of our overall winter raptor population

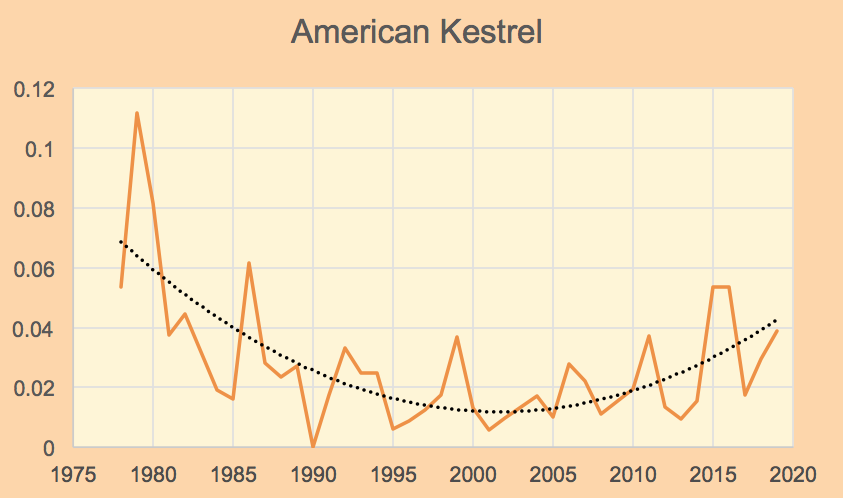

Species Whose Numbers Have Been Increasing: Five types of diurnal raptors have enjoyed winter population growth here in the past 40 years. This includes all three of our region’s most frequently seen falcons – kestrels, merlin, and peregrines.

This is somewhat of a pleasant surprise, because the kestrel population has been and is still declining across the United States, and our resident population had been declining until the late 1990s.

Kestrels remain the most numerous of the falcons across North America. And, at least during the winter months, they are the most common falcons in our area, too. It is nice to see them doing well close to home!

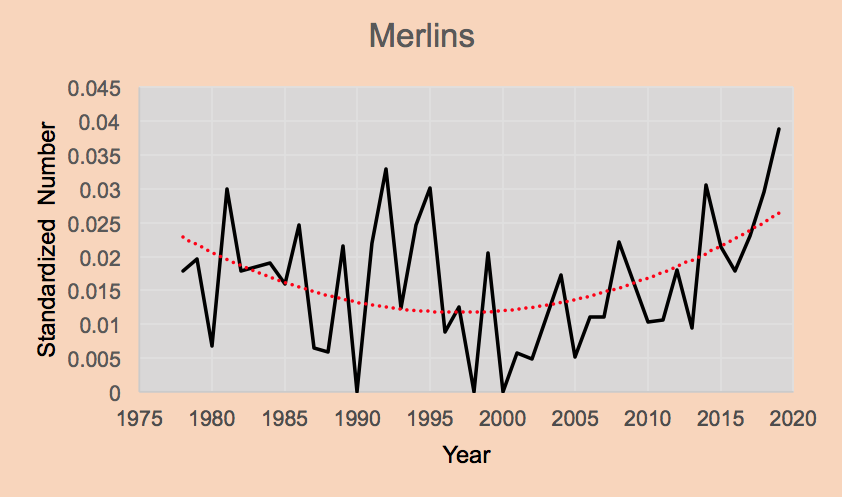

Merlin, who held steady from the late 1970s through the late 1990s, has become more common since then. This rise mimics that seen across the country. Again, a good reason to celebrate! (The trendline appears to dip from 1978 to 1997, but the appearance is misleading: the annual fluctuations are too large for the trend to be significant.)

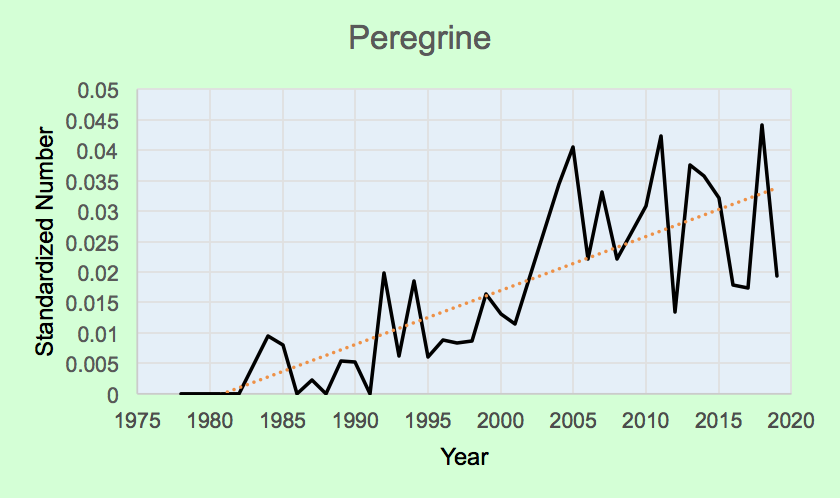

And, last but not least for falcons, peregrine numbers have been rebounding here and across North America since DDT was banned in the early 1970s.

The remaining two species that we are seeing more of include an accipiter and an eagle.

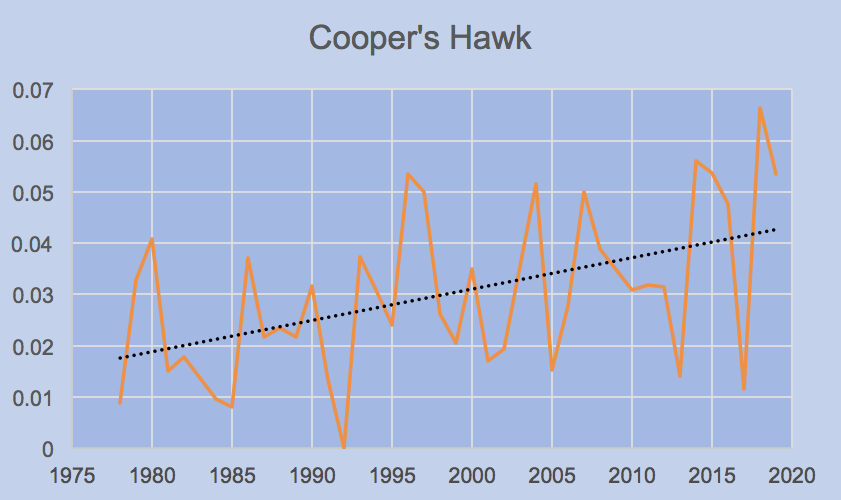

Cooper’s Hawk numbers have been holding steady across North America, and so ours are bucking the trend in a positive direction.

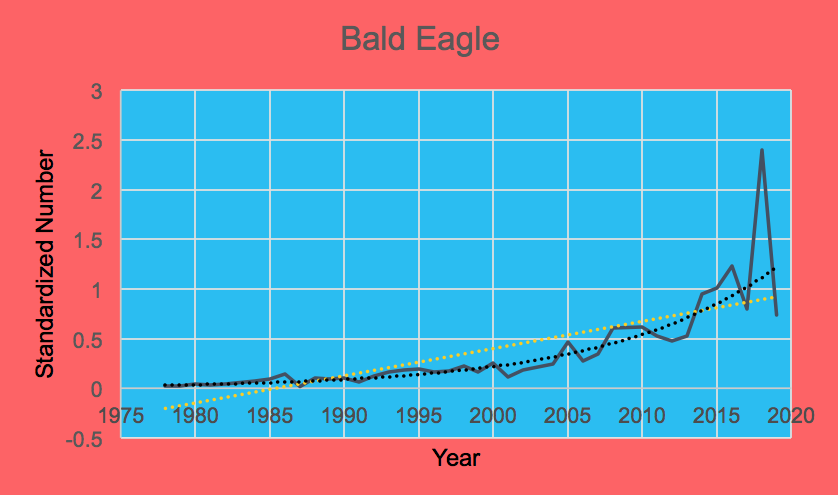

Finally, I saved the best for last: the biggest success story and the largest increase among all our raptors involves the much-beloved Bald Eagle. They are exponentially increasing in number: whereas there were a total of 78 Bald Eagles seen during the Count 1978-1987 and 357 in 1993-2002, there were 1634 observed in the past ten years! This parallels the national trend for these magnificent birds.

This increase means that, although in they only accounted for 10% of our winter raptor observations in 1978-1987, during the past ten years they have accounted for a full 49%!

In sum, the Count data indicates that the health of our winter raptor population is quite good. Only one of our common species – Northern Harriers – is in decline here, while five species, including our two most common, are increasing in number. Given the joint pressures of climate change, habitat loss, declining insect populations, etc., I was worried that I would find far worse. Since I so enjoy seeing Northern Harriers, I feel energized and even more committed to protecting the marshes and wet grasslands that they need. I hope that you feel the same way!