By Kim Adelson

High on my list of “things to love about living in Western Washington” is our great abundance of winter waterfowl. Maybe because I used to live far from the coast, in a rather dry area with few lakes or rivers, I continue to be enthralled by the number and variety of ducks and geese that we can see here as the weather turns colder. Due to length considerations, I am going to discuss only ducks in this article. I have found them not only a personal joy to behold but also a great way to introduce birdwatching to novices. They certainly are easy to spot! So… which species are you most likely to catch a glimpse of in the South Sound this winter?

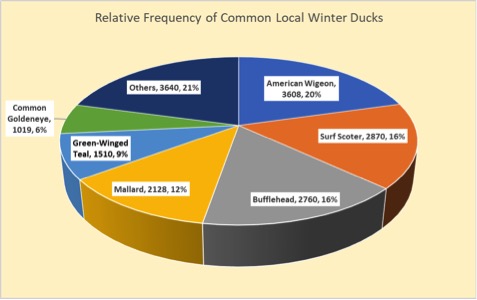

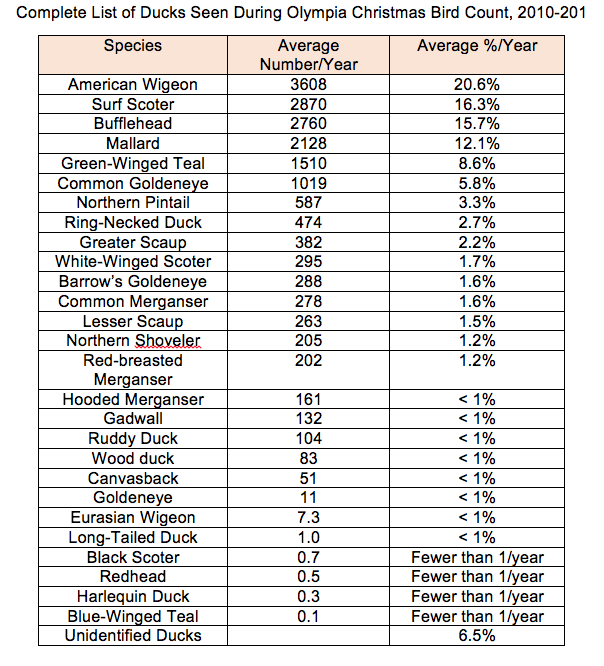

An average of 17,535 ducks, representing twenty-seven species, have been observed during the past 10 years Olympia Christmas Bird Count. Individuals from just six types make up just shy of 80% of the total:

Of course, which you see depends upon your location. You’ll likely find Surf Scoters along the coast of Puget Sound; in more protected coastal coves and estuaries you’ll also find Common Goldeneye. American Wigeons, Buffleheads, Green-winged Teal and Mallards are more eclectic and can be found in both salt and freshwater, especially where it is very shallow.

Three of our most common ducks – Mallards, Green-winged Teal, and American Wigeons, dabblers: that is, they often forage “butt up” white floating on the water’s surface. Several other characteristics make them easy to tell apart from the others. First, they are very buoyant and float high in the water. Second, since they have longer wings than many other ducks they do not need to run on the water in order to take flight. A third, often frustrating, characteristic is that, although the males are quite brightly colored and distinctive, the females are a similar mottled brown. Female GW Teal can be identified by their very small size, green speculum patch, a cream-colored stripe near their tail and a uniformly dark bill. Female mallards are large and have bills that are a patchwork of orange and brown. Female American Wigeons have a greyish head with a darker patch around their eyes; their bills are a light grey with a darker tip.

Will we continue to have such bounty in the future? Unless we act quickly and forcibly, climate change – with its concomitant habitat loss, extreme temperatures, droughts, forest fires, sea level rise, and increased acidification, etc. – is predicted to result in decreased duck populations in our area. In many cases this is due not to changes in our region’s winter climate but rather to loss of the birds’ summer range in the far north as the Arctic warms: if they can’t breed there, they can’t migrate here. Local ducks that are at high risk of losing their far northern summer ranges include Surf Scoters, Bufflehead, and Common Goldeneye (3 of our most common ducks!) as well as Greater and Lesser Scaup, White-winged Scoter, Barrow’s Goldeneye (who also risk losing most of their winter range here). In addition, American Wigeon, Green-winged Teal, Northern Pintail, Ring-Necked Duck, Common and Red-Breasted Merganser, Gadwall, Long-Tailed Duck, Harlequin Duck, and Black Scoter are at moderate risk due to loss of northern breeding grounds. To make matters worse, whether or not they are at risk in other areas or nationally, due to climate change the South Sound region specifically is slated to lose most of its winter habitat suitable for American Wigeon, Green-winged Teal, Eurasian Wigeon, and Black Scoter, and also to lose most of its summer Hooded Merganser habitat. All in all, only 7 of the 27 species (Mallard, Northern Shoveler, Ruddy Duck, Wood Duck, Canvasback, Redhead, and Blue-winged Teal), which combined comprise only ~15% of our winter ducks, are predicted to avoid the ravages of climate change.

This is a lot of motivation for me to do what I can to combat climate change. I hope it inspires you as well.