Red-shafted Northern Flicker

Colaptes auratus

By Sharon L. Moore

Who among us isn’t delighted by Northern Flickers? While the Red-shafted live year round in the West, the Yellow-shafted may be present here during the mating season, though they generally live in the Eastern U.S. Since these birds thrive in nearly any habitat with trees, we often spot them locally in our deciduous woodlands and suburban conifer forests, even on our lawns. Along with other common birds such as Dark-eyed Juncos and Chestnut-backed Chickadees, the Red-shafted Northern Flickers often visit our feeders in winter. Bracing themselves with their tails against suet block holders, they use their long bills to peck forcefully, foraging on the suet as an important source of fat and protein.

There’s no doubt these birds’ bright color displays draw us to them. As one of eleven woodpecker species in North America, they carry bold markings that help us easily identify them. Sporting a black crescent bib on its chest, this twelve-inch-long, sturdy bird has a brown cap and gray face with the male displaying a distinctive red mustache. The brown back is sprinkled with black bars and the beige chest carries black dots. Completing the flicker’s stunning appearance is the white rump and bright red-orange feather shafts showing on its wings and tail when it flies. Once scientists established that these bright colors come from the carotene in fruit the birds eat, they then posited that the striking red-orange wing and tail coloring likely helps protect flickers from predators. At any disturbance, the bird flashes these bright colors as it bursts into flight, startling potential predators and increasing the bird’s chance of escape. Recently at our backyard feeders I observed two flickers about to be attacked by a low-flying Cooper’s hawk. Both flashing red-orange when they took flight, they confused the hawk, successfully escaping in the nanoseconds it took the hawk to recover.

During spring, summer, and fall, Northern flickers’ diets include a wide range of choices. As fruits, berries, nuts and seeds appear, the flickers are assured of adequately feeding their newly hatched young. To increase their calorie-rich food intake they also commonly peck away on the ground, using their bills to find beetles and beetle larvae, termites, caterpillars, and particularly their favorite gourmet cuisine – ants. Even tree-dwelling, wood-boring insects don’t escape the flicker, however, as it is able to hear movement 18 inches deep in the wood. This acute hearing allows the bird to chisel into the tree to capture insects and their eggs.

With spring mating season arriving, as you read this, the flickers are increasing their vocalizations and noisemaking. Walking in the woods we may hear their piercing, sharply descending “peeahr.” We may also hear their call that sounds like “wake up, wake up, wake up.” And let’s not ignore their drumming. Looking for objects that let them make noise as loud as possible, metal light poles and roof gutters are favorites that help them communicate with each other, advertising for a mate and defending their territory. If you’re hearing entirely too much drumming this spring, try hanging strips of mylar around the noisy location. That may encourage the flicker to move on.

In the breeding season from March to June the male and female engage in a territorial dance called a “fencing duel.” The two birds face each other on a branch, their bills pointed upward, and bob their heads while drawing a loop or figure-eight pattern in the air, often calling “wicka, wicka.” Once the pair has bonded, the male will help the female find and excavate the nest, with the male contributing most of the work. This is highly unusual in the bird world as females usually carry all the nesting responsibilities. The flicker pair may claim a previous nest hole after making minor repairs, or they may excavate a new nest hole in a dead or dying tree, aging utility pole, fence post, or siding on a house or out-building. They’ll spend up to 14 days hollowing out the nesting hole depending on the density of the wood. Nests are generally 6 to 20 feet above the ground though they may be as high as 100 feet.

As the pair begins to prepare for a new family, the female lays 5 to 8 eggs on the wood chips they produced during excavation of the nest. Both male and female incubate the eggs for 11 to 12 days. Once the nestlings emerge, both parents feed them in the nest for 24 to 27 days. At this point they are extremely vulnerable to predation. Even after the surviving young fledge, the parents continue to feed them until they are able to follow their parents to foraging sites and find their own food. This excellent parenting by the bonded pair insures a good survival rate of their young and helps keep families together. For many years we have observed successive generations of flicker parents bringing their fledglings to our property, patiently teaching them to use their tails against our suet block holders in order to feed.

The Red-shafted Northern Flicker does not migrate long distances; however, it definitely follows insect populations and ripening of tree fruits. So, though it may disappear for a time in summer, it generally returns in the late fall. To encourage these flickers to come back to us there are a number of helpful steps we can take. Protecting undisturbed wooded areas that harbor dead or dying trees is important. Large trees offer the opportunity for large nesting holes and smaller trees rot faster, attracting insects that provide food for flickers. Since there are chronic shortages of adequate trees and holes for flickers, we can build and install nest boxes designed especially for them. Google Washington Fish and Wildlife Nest Boxes for Birds for box plans. If you build a box or two, be sure to attach a metal guard around the nest hole to keep predators such as squirrels and Steller’s Jays from raiding the nests of eggs and young – a serious problem. Should we see ant colonies, let’s leave them for the flickers to find and harvest. Let’s also leave pieces of fruit on native and non-native trees for flickers to eat year round. Finally, let’s discipline ourselves away from using pesticides, especially insecticides, anywhere on our properties. We can also encourage our neighbors and friends to do the same. Make an effort to request that city, county and state park personnel honor the fact that pesticides and insecticides endanger birds. Remember Rachel Carson’s warnings in her blockbuster book Silent Spring, published in 1962. Largely through Carson’s and other scientists’ intense efforts, after an ongoing Congressional battle, DDT was finally banned in 1972 in the U.S. though some countries continue to use it. Still today, it’s worrisome to know we live in environments permeated with thousands of generally untested, potentially deadly chemicals.

Enjoy the gentle demeanor and flashing colors of these lovely Red-shafted Northern Flickers. They are a gift to us all.

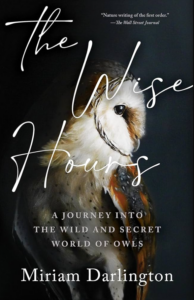

Photo credit: Male Red-shafted Northern Flicker, by Tom Koerner/USFWS, Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Northern_flicker_on_Seeskadee_National_Wildlife_Refuge_(34055485266).jpg