Armchair Birding: Vicarious Travels with Roger Tory Peterson and James Fisher in Wild America

~ Anne Kilgannon

As you flip through your Peterson guide to check some field mark—say, the presence of an eye ring or patch of white or the shape of a bill—do you ever wonder about the writer/artist himself and how he came to know so many birds so intimately, in such crisp detail? His first guide was published in 1934 when he was still a young man but he had been birding for years already, ever since a teacher had introduced him to Junior Audubon Club materials. Birds—seeing them in the field, then later capturing their essential forms in drawings and paintings, getting to know their ways as wondrous living beings (instead of shooting and skinning them as many practicing ornithologists automatically did), Peterson early dedicated his life to bird study. He was besotted, driven, inspired. His British friend and fellow-birder James Fisher recalled that when any conversation strayed from discussions of bird lore, Peterson would get a far-away look and only snap to attention when birds came back into focus. He had an insatiable desire to know birds, as many as possible.

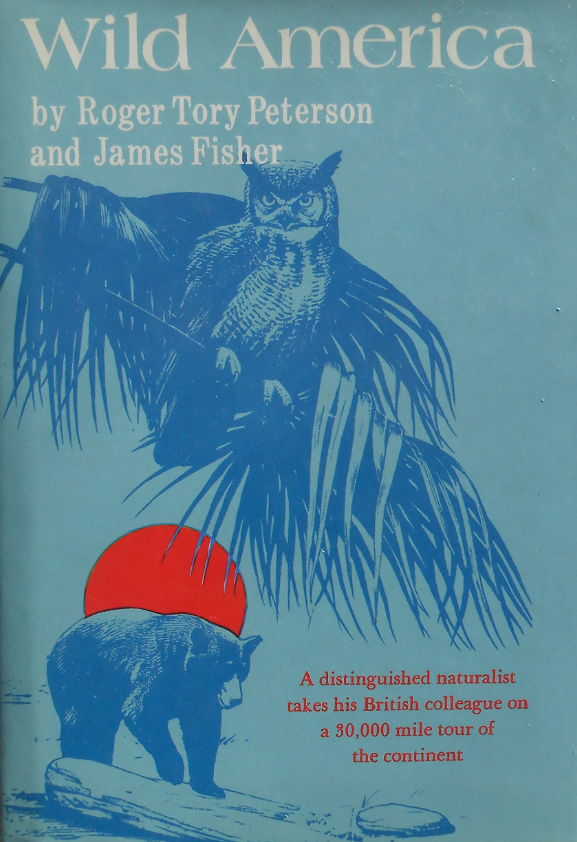

Roger Tory Peterson went wherever birds were—that is—everywhere, with cameras, notebooks and binoculars. Eager to share his knowledge and passion, in one stellar one hundred-day period in 1953* he and James Fisher traversed the perimeter of America in an epic dash to see as many birds as possible, from Newfoundland to New England, southward along the ridge of mountains separating coastal areas from the inland, to Florida and through the south to Texas, dipping into Mexico and then swinging northward through deserts, mountains, redwood forests, crossing the great Columbia to enter the Olympic rainforests and ending up on Alaskan islands stretching toward the Bering Sea. They photographed and filmed their adventures and discoveries and piled up copious notes as well as additions to their life lists and a record number of species seen to date. You can travel with them in their book, Wild America, subtitled “The record of a 30,000 mile journey around the continent by a distinguished naturalist and his British colleague.” Nothing compares with birding with the birding master; reading about it comes a close second.

The pace was both exhilarating and exhausting. Peterson had choreographed the whole trip on a tight schedule to make the most of their time, as well as slotting in meeting up with other noted birders and guides to help them find the special birds of every region—a veritable list of birding who’s who of that day. Weather plays a vital role, regular meals not so much; they subsist on Cokes and road food and sleep in real beds only sometimes. Roads range from excellent to faint trails, gas stations were not always where needed, sometimes desperately so. Car troubles, thirst, heat, venomous snakes, storms: they persevered and the bird counts multiplied; it is astonishing how many and the great variety they managed to see. It helped that they had lists of expected species for each place and that they had assiduously studied their field guides and seemed to know every feather of every bird possible, where it lived, how it lived and all its life phases from egg to maturity. It helped that Peterson knew the calls, chirps and whistles of hundreds of birds and could direct their attention into deep foliage accordingly. It helped that both Peterson and Fisher were widely experienced world-class birders, keen and dedicated, and also tolerant of each other’s foibles and needs. They were friends throughout the venture and despite the intensity and challenges, remained a team while subtletycompeting with each other. It was all about beloved birds, after all.

The book is a deep dive into a bygone era of birding before the advent of lightweight binoculars, cameras and cell phones, Internet birding websites, and REI-style camping equipment.* Reading, I was pricked by my awareness that this adventure had a buoyancy now shadowed by our own time’s register of the anguish of climate change impacts on bird life. The trip occurred before the publication of Silent Spring launched a new phase of concerted conservation efforts—although crashing populations of California condors and other species were already concerns. Peterson played a role in corroborating the work of Rachel Carson but the widespread use of DDT is not mentioned as an issue here; all that is to come. This may have been a golden era of birding, when preserves and other programs were greatly facilitating bird life and other dangers were not yet rising into view.

Peterson and Fisher were keenly aware of the need to protect habitat as foundational for bird survival but the continent did not yet feel paved over with human infrastructure. Although Peterson did have some foreboding as he witnessed a parade of logging trucks hauling giant timbers from Northwest forests, there was still very much a wild America to discover and explore in the mid-twentieth century time. How much still survives? Even if we are now in the Anthropogenic world, there are still birds to search out, Peterson guide in hand, to enjoy and be dazzled by, to witness and protect. To hear their song and respond. Peterson himself still inspires and instructs; his adventures still resonate. What a time they had!

* Meanwhile, also in the spring of 1953, Margaret McKenny and Leo Couch launched the Olympia Audubon Society, the forerunner of Black Hills Audubon.

* Also, a time before much thought was given to inclusion and respect for “others,” that is, other than white male birders. Their treatment here is uneven: some women are noted as experts in their fields and are included as trusted guides but they are acknowledged as rarities. Some native peoples are also seen as having a deep knowledge and wisdom concerning the natural world while are others are dismissed with little understanding of their history. Black people are given very slight and derogatory notice. Reading accounts from past times can be a measure of how much has changed, sometimes for better, and how some remarkable people are nevertheless unthinking products of their time in other areas.