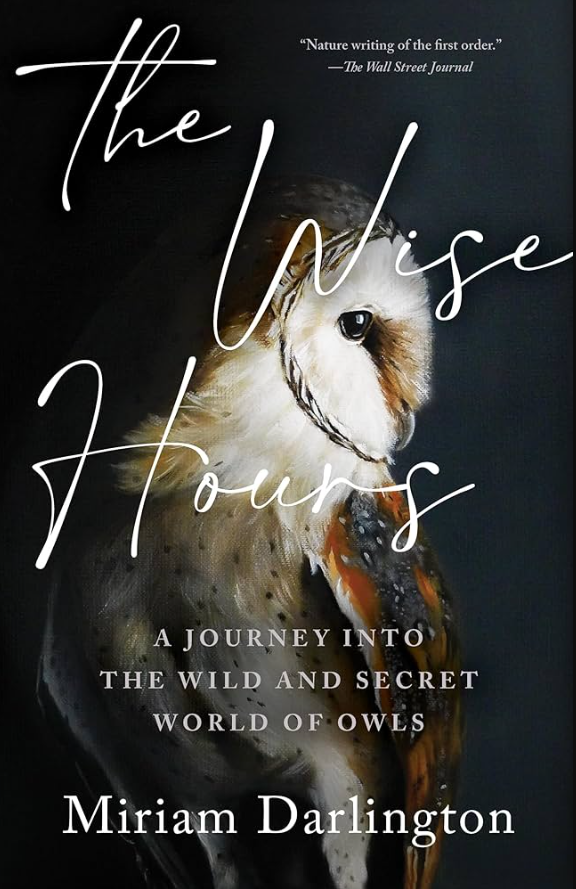

Armchair Birding: The Wise Hours: A Journey Into The Wild and Secret World of Owls, by Miriam Darlington

~ Anne Kilgannon

One of the most magical moments is awakening in the night to the sound—sometimes tantalizingly near but mostly distantly faint, from no discernible direction at all—to an owl hooting into the darkness. Calling to a mate or just expressing—what? I have never seen an owl in any nearby tree, although I suppose they could be there without my knowledge. But I just thrill to the idea that one may be present, or passing through, “out there.” Owls, hooting or silent, are the essence of wild nature; it doesn’t matter if I don’t see them. Miriam Darlington would agree with everything just said, except she would insist that finding and seeing owls is essential and too wonderful to not pursue with determination and aided by a deep knowledge of their ways. She’d be pulling on her wellies* and slipping outside in a flash, black night, rain or whatever, if an owl let itself be known within her range of hearing. And she’d probably find it, already familiar with its habits and preferences.

*Wellies are Wellington boots, named presumably for the great English general who defeated Napoleon, what we would call rubber boots here.

As she recounts, Darlington became more and more obsessed with owls, with learning as much as she could about each species in her English homeland, but also in finding ways to experience being with owls, seeing their haunts, their nests, their flight and hunting techniques. Volunteering for owl research projects, visiting sanctuaries, waiting patiently near roosting sites, she could hold one for banding, feeling its surprising weightlessness in her own hands, examine its complex ear structure that could pick up and triangulate the sound of a vole munching withered grass under deep snow, and marvel at the lethal power of talons and beak. And most of all, to look into its fathomless golden eyes.

Mostly golden, but also orange eyes! And some brown eyes. Darlington began her study quest with barn owls, not too far distant from her Devon home and, at first, intended to learn all she could about owl species resident in Great Britain, but when opportunities arose to explore owls in other territories, well, she couldn’t resist! As she discovered various international branches of owl study and networks of owl lovers she went as far afield as Serbia, Finland, the French Alps, and Spain. Each place was a destination to experience a new kind of being and discover, as well, compatriots as enthralled as she with these almost-mystical birds. Each new habitat explored, each search for a new species, came with its own layer of local cultural associations and mythologies embroidering the science, enriching the encounters with both owls and humans. It gave me great hope to learn there is a vibrant worldwide network researching and working to save owls and the places they inhabit, a narrative thread that developed as a major theme of Darlington’s book.

Conservation science and the work of its community of practitioners formed the substantive core of her book but there is so much more. Her writing combines three threads, all woven together and supporting each other. The Wise Hours is catalogued as a memoir, which at first surprised me, but as I read I could see why that was so: she describes how her intrigue with owls slowly and then absolutely took over her life, pushing her to travel broadly and arrange other responsibilities to fit around owl study. (At times I worried about her marriage surviving this competition! Owls are very compelling.) Another thread, also eye-opening, was a kind of travelogue, an adventure story as she discovered places she had never expected to see. Reading about her experiences in Serbia was a revelation, learning how the French bird culture was so different from the Brits, and plunging into the boreal forests of Finland was a vicarious thrill. And, of course, braided through every story were the owls, tiny elfin ones, giant eagle-size ones and everything in between; soft feathered but sharp taloned, sweeping into the night sky, calling and screaming, hooting or silent. Each of the eight chapters is devoted to a species. There is so much to learn, to experience.

Besides actively stoking your own desire to experience owls, now I’ll leave you with one of her apt terms that applies to all bird study: “earsight.” We regularly sharpen our bird-watching eye-sight with binoculars and spotting scopes, but Darlington reminds us that listening—developing our earsight—is just as, if not more, crucial for studying nocturnal species. And it brings us such joy! Hearing a string of twittering song emanating from a bare-branched street tree, just the other day, I finally spied a finch on a high branch expressing his opinion of the weather. His cheer lifted the fog and my mood. Just as hearing an owl in the night gives me a thrill, a sense of mystery and hope, as a good as a vision of possibility.