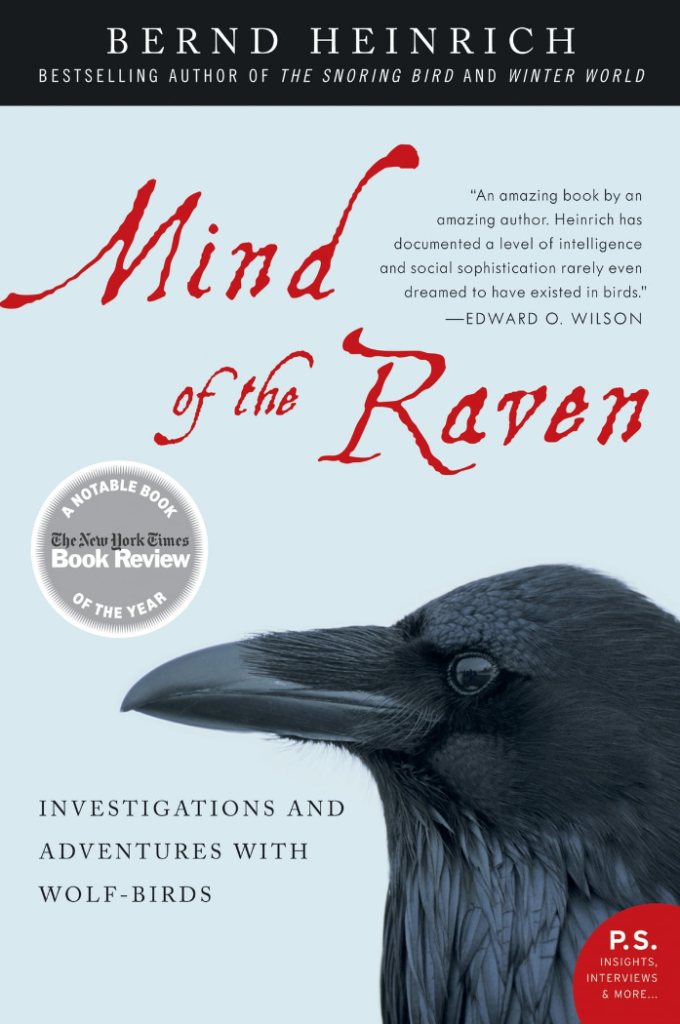

Mind of the Raven

by Bernd Heinrich

By Anne Kilgannon

Let me begin with a story about my recent less-than-scientific behavior. I was wandering around a clearing in a patch of Douglas fir mixed forest when my attention was drawn to the raucous chatter of several ravens grouped in a rough circle high up in the trees. As they called to each other I surmised that my strange human figure might be the object of their remarks. Upon impulse, I replied to their quorks with my own, and when they shot back, I continued. And they continued; we called to each other, one-to-one quorks, or two- or three- to two or three replies for about twenty minutes! I couldn’t see them very clearly against the dark branches of the trees but I could see excited rustling moving those branches. I tired before they did; they only flew off after I had stopped responding. Wow, what was that all about?

I went home and shuffled through my bird shelf for a book I had cached there a while ago—a very raven-like thing to do, as I found out—if I think of my book habits as pieces of meat to be saved for later, as needed. Sustenance, for sure! The book I was looking for was Mind of the Raven by one of my favorite naturalist authors, Bernd Heinrich. The subtitle exactly describes Heinrich’s approach: “Investigations and Adventures with Wolf-Birds.” If he had been standing in that clearing with me he would have asked dozens of questions to unpack the ravens’ behavior and compared that peculiar experience with years and years of his own encounters with ravens, and would have been able to back up his speculations with reference to his vast readings of the pertinent literature, and maybe even shimmied up one of those towering trees to get a closer look. He probably would have somehow enrolled me on the spot in some exacting study or experiment to carry out a research project he’d been contemplating for years… or one that emerged full-blown just then. What he would have had was a wealth of observations and issues that still puzzled him, even after all these years, about just what those ravens were saying and doing.

Are ravens intelligent… and what exactly is intelligence? Bernd ponders—and then devises tests to discover whether ravens think anything like the way humans do; say, do they plan ahead and learn from experience? Prompted by my reading, I wondered, were the ravens playing with me, or testing to gauge me as a threat, or alternatively, a possible source of a treat? Have other humans left trails of food, some delicious and some may be lethal? Or was I just strange, a random two-legged creature new in that environment that should be treated with caution, or some kind of thing they had noticed before but only in passing? Was my raven-black coat a factor, a possible point of contact?

In a very abbreviated way indicated by this list, this barrage of questions would have erupted from Bernd had he been present. His method of investigation of raven behavior leaves no possibility out. In fact, he is very raven-like himself, picking up every stick, poking his beak into every crevice, watching every move from close up to far-away dots moving across the sky. His “home” ravens in forested Maine to ones in Yellowstone Park or Germany or desert areas have merited Bernd’s attention and comparison; all ravens are fascinating to him and add to his knowledge—and questions to further explore.

Ravens are such complex creatures, singularly and especially in social groups. Bernd’s experiments with both wild and semi-tame birds are so imaginative and nuanced. And he always gives them the benefit of the doubt; if their behavior is puzzling, new, or contrary to what they might have done the week before, he just keeps trying to understand them and stretch his own mind to reach theirs. Any bird watcher, whether viewing eagles or hummingbirds, will look at birds differently after reading Bernd’s accounts. True, ravens as Corvids are among the cleverest birds on Earth but his close observations and relentless questioning and quest for meaning will inspire anyone to look more deeply, interpret more broadly, and with more granular attention the endlessly fascinating life of birds, all birds.

And as we take note of all bird behaviors and interactions over the seasons and years, we get closer to another revelation: how we are kin. How, in so many ways, we and birds are not so very different in our ways, our needs, our place here in the world. It’s both humbling and exciting: now if only we too could fly!