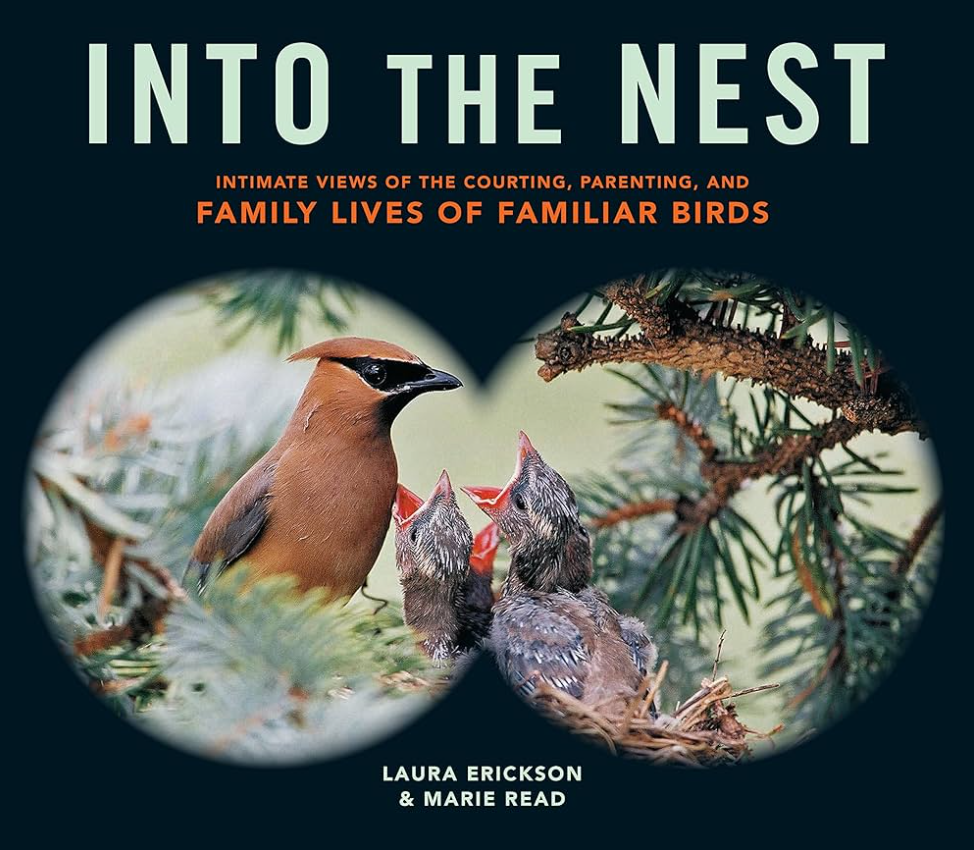

Armchair Birding: Into the Nest: Intimate Views of the Courting, Parenting and Family Lives of Familiar Birds, by Laura Erickson and Marie Read. Published by the Cornell Lab.

~ Anne Kilgannon

We were in our friends’ garden when two eagles appeared overhead wheeling and calling with their high-pitched screams, clasping feet for a brief moment and then disappearing into the distance. Our friend asked if we were witnessing their mating, something I would have wondered myself just days ago. But I’ve been reading Into the Nest: Intimate Views of the Courting, Parenting and Family Lives of Familiar Birds. I had learned something even more fascinating from this gorgeously illustrated book, that no, the eagles were sky dancing—such an apt description—a part of the prelude to mating: “an essential aspect of courtship” that synchronizes their hormonal levels. The mating takes place on the ground or on a sturdy branch that can support such large birds. (Reading this was one of several “of course” moments that filled in a detail that made immediate sense, now that I thought about it.) But what interested me even more was this notion that courtship rituals like dancing, head bobbing, singing, twig presentations and the like actually tuned birds physically to each other, releasing chemicals in their bodies that readied them for mating. If this was true for birds….was it true for more than birds? Quite likely, it seems to me. A good question! The book is filled with provocative bits like that, stirring thoughts and wonderment.

The real marvel as I read bird-by-bird descriptions of “Courting and Mating” and “Enter the Egg” and then “Nesting and Parenting,” ending in the fledging and maturation of the chicks, was the entwined story of evolution and how these complex patterns worked for each bird species, producing the new generations in myriad ways that best suited their habitat conditions and individual needs. That the imperative to reproduce and pass on one’s genes drives so many behaviors, and with such variations and accommodations and quirks, was revelatory.

The “aha moments” rolled out, one after another. For instance, how a female bird sizes up a male’s “fitness” involves his ability to sing and sing and sing, sometimes his one special song and sometimes, like the mockingbird, a medley of dozens of calls, trills and melodies borrowed and burnished. Or it could be the sheen on his feathers, that patch of color or white on a spread tail or wings, or that flash of black on shoulders or a snazzy tuft in a crest. Or perhaps his dance moves or his sky-rocketing and dive-bombing abilities. Or—and I admit I found this almost humanlike—his tender offering of just the right twig for a nest. As I read about all these strategies, I felt the long stretch of evolutionary time that selected—or discarded—the code of strength over hidden weakness of body and behaviors that added up to survival and perpetuation of the species over time. It was astounding to contemplate.

The many ways this unfolds are complicated. Male hummingbirds are obsessed with territory. But they are lousy husbands and absentee fathers. But their ferocious defense of their chosen place protects the female and her eggs and then the babies so she is content, we might say, to put up with his brief attentions. She seems to know that the patch of flowering plants nearby under his watch will be available to her and it will be enough. Other bird fathers are much more involved: some feed the female as she stays on the nest to brood the eggs and the newly hatched naked chicks. Some will even take a turn keeping the home fires warm so the mother can stretch and take a break. Some will attend to housekeeping, removing the fecal droppings. Some will help feed the chicks and even stay with fledglings when the mother leaves early to begin a new nest. Or not, but it works out, bird by bird.

Nests or what passes for a nest—a mere scrape on the ground for killdeers—were another area of investigation. What makes a home? A huge pile of twigs high in a tree for an eagle or hawk or heron, or something smaller woven deep in bushy growth, or a mud concoction plastered to an underpass or building ridge, or some shavings deep in a hollowed cavity in a tree. The most striking are the phoebes who build their nests on pipelines in Alaska where there is nothing else for an anchor. The effort involved ranged from a few dashes of the feet, to cedar waxwings being clocked at five or six days of construction amounting to 2,500 individual trips bringing just the right materials for their nest. Each according to size and a need for safety, but also reflective of the size and shape of beak and feet: what the beak can carry and construct and what the feet can grasp—or not. The shape of the nest often corresponded with the shape of the bird, literally, as the prospective mother molded the bowl of the nest to her body using her body. And the cleverness of using spider webbing as glue, and the chutzpa of plucking hairs from a sleeping dog or seizing long horse hairs or other materials scattered about by humans, even old cigarette filters and other garbage. I was most astounded to learn that the offspring of cavity dwelling birds had adjusted their maturation process to the higher levels of CO2 that builds up inside a tree (but is somewhat mitigated by the passing in and out of the parent birds bringing food.)

All this preparation for the coming of the next generation is critical. The close up photos of the tiny naked baby birds, their brightly colored gaping mouths that parents could see even in dim lighting—there is a reason for bright white eggs in darkish cavity nests as well as those almost luminescent mouths—that brings us intimately into scenes we should never attempt to witness for ourselves. (Many babies if too closely observed will escape their nests and thus perish.) We are allowed glimpses of the effort involved in hatching, and then of the work of the attending parents, regurgitating food down hungry gullets, how the feathers develop and unfurl within mere days, how the tiny wings are exercised, and how the siblings jostle and tumble about. We’ve been privileged to observe the next generation readied to launch!

This collection of bird profiles, anecdotes and images deepens our knowledge of birds and our sense of wonder at the surprising variety and ingenuity involved in the cycle of life. This is a book to return to again and again, for the photos and the clear explanations of all that lies behind the astonishing ways of birds. As I watched a raven scribe a line across the sky, carrying one twig and silently disappearing into the trees, I felt an intimacy with that aspiring new family new to me, a revelation.