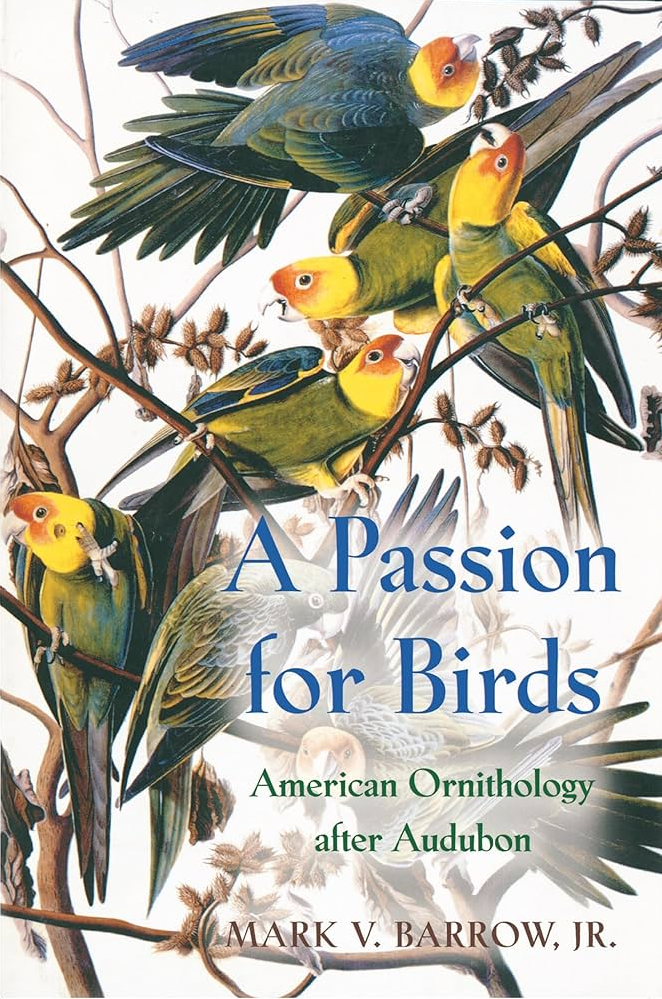

Armchair Birding: A Passion for Birds: American Ornithology after Audubon

by Mark V. Barrow, Jr.

~ Anne Kilgannon

The Carolina parakeet with its bold plumage of orange, bright yellow, red and olive green had once flourished in the lush forests of the southeastern part of what became the United States. But as settlers moved in and cleared their forest habitat and declared the birds a menace to their crops, the much diminishing flocks were pushed back into mere remnants of their former range. While they managed to hang on as a species in patches of the back country, a new danger arose: ornithologists and their networks of procurers set their sights on “collecting” these striking and increasingly rare birds for their museums and for their private possession of bird skins, nests and eggs.

As Mark Barrow explains, “Collectors of all kinds have always eagerly pursued rare or unusual examples of the objects they are amassing. Thus in a dangerous downward spiral repeated for a disturbing number of bird species, a decrease in the number of parakeets served to increase their value to collectors, whose predations further decreased the remaining population. Faced with the impending extinction of this and other species, the taxidermist William T. Hornaday’s urgent advice reflected the dominant ethos of the culture of collecting: “Now is the time to collect.” As the final stronghold of the Carolina parakeet, Florida became a mecca for naturalists seeking to capture the few surviving examples… Among those anxious to collect the rare species was the young ornithologist Frank M. Chapman.” Barrow describes in detail how many parakeets he killed even as he struggled with his foreknowledge of their impending extinction. The collecting imperative won.

Yes, the same Frank Chapman who was a longtime curator at the American Museum of Natural History; who became a leader in the bird protection movement; was the founding editor of Bird-Lore, the official publication of the Audubon societies, where he also served as a board member for state and national Audubon associations and the instigator of the Christmas Bird Count, the long cherished substitute activity and budding citizen science foray that aimed to replace the tradition of the annual holiday bird slaughter.

So, here we have a history of the early bird protection movement entwined with the story of the movement to develop the scientific study of American birds and how the professional needs and fixation on taxonomy both catalogued the bird population of the continent and played a role in destroying its objects of study. Ornithology was a budding science practiced through the barrels of guns. A bird “in hand” was a bird that could be studied, measured to fractions of inches, weighed, had its feathers examined and then preserved with arsenic in a museum drawer to be compared with hundreds of others of its kind in other drawers and collections. It could be traded, displayed or forgotten, but it would never see the open sky again.

A bird’s way of living, its song, family life, migration pattern and other quirks of behavior were, in this scheme of study, unimportant. The biggest question of that day was whether it was an example of a species or a sub-species. Was it slightly larger or smaller than its fellows, or slightly of a different coloration or some other detail that might justify tagging it with a new name and add the sheen of discovery to its examiner. How much did naming rights drive such speculations and distort the science ornithologists were so keen to establish as their territory alone? Barrow charts the complex relationships woven and shredded between taxidermists, natural history merchants, eager boys with guns, and the sport hunters who supplied the museums and other collectors with hundreds of specimens in a brisk trade for decades. The establishment of the American Ornithologists’ Union in 1883 with its two-tiered membership that separated the professional scientists from the heterogeneous class of bird procurers that supported bird study was a pivot point in this movement. As ornithologists were drawn into the protection movement (as early conservation attempts were called) this divide sharpened: the professionals could collect birds for “science” but pot hunters and others were banned or corralled with rules and regulations that applied only to their pursuits. The new laws prohibited plume hunters and other predatory actors from their slaughter—a huge win for birds—but exempted the Frank Chapmans from such restraints. While pouring scorn on fashionable women with their feather-bedecked hats, the hundreds of drawers full of dead birds were not to be acknowledged. That all ornithologists were men—to be clear, white men—was also taken for granted.

As much as the professional birders strove to control the study of birds as their own privilege, more and more ordinary people were drawn to bird watching as guides were developed, binoculars became available and the world of nature became more precious as it fragmented and degraded under the pressure of urban development and industry. That’s a whole other chapter explored by Barrow: the balancing act between the scientists and the enthusiasts, the collectors and preservers, the lovers of birds in their natural settings and birds under the microscope. It’s an intriguing read, a development that leads to today’s discussion of the empowerment of citizen science, new conservation practices including habitat restoration, arguments about the role of predators, and who makes the decisions and who is included in the conversation. We are part of this story.