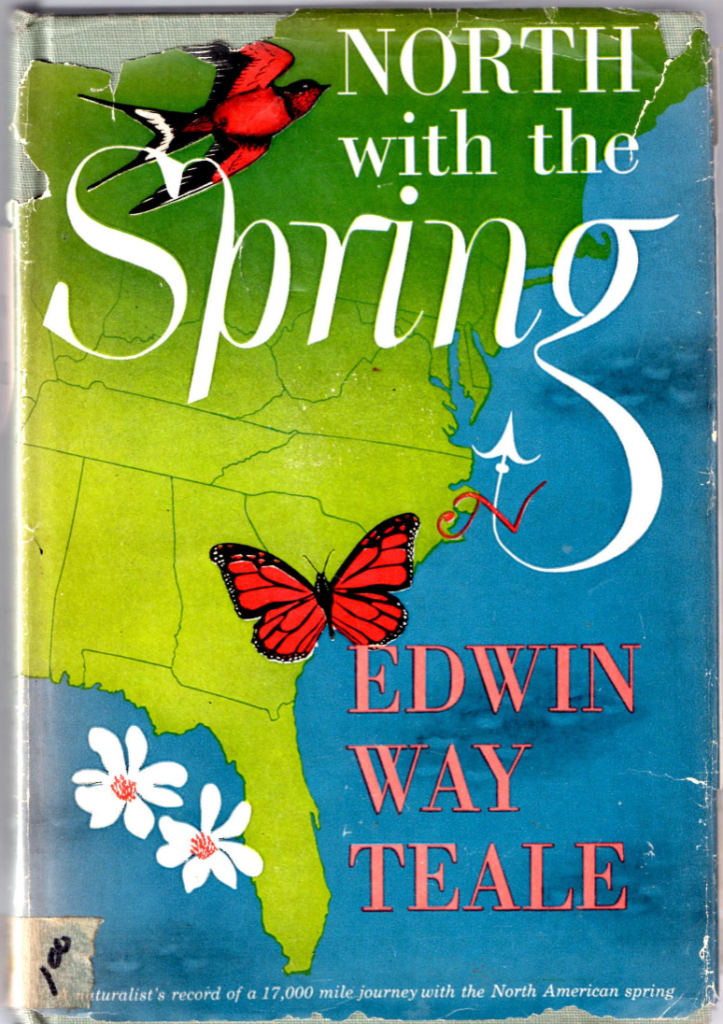

Armchair Birding: North With the Spring, by Edwin Way Teale

~ Anne Kilgannon

Edwin Teale and his wife and collaborator Nellie had been planning this long journey of exploration and discovery—17,000 miles beginning from the tip of Florida and heading north in a zigzag trek to the Canadian border—for many years before pointing their car south from their home in Connecticut to launch this adventure Valentine’s Day, 1947. Their car was stocked with notebooks soon to be full of their observations, camera equipment, guide books, maps, and contact information of individuals expert in their various locations who could reveal secrets of places ordinary tourists would never see. Between them, the Teales carried their own areas of expertise: Edwin’s close study of insects, his knowledge of geology, geography, and history, and the vast network of those writing and working in the field on natural history subjects then and from its earliest expressions. Nellie brought her depth of bird and botany wisdom and experience, and her guiding watchwords: “Go slow and see more.”

I confess I have been in few to none of these places so their descriptions were fresh and even astonishing to read. I am unlikely to find myself poling a raft-like boat through alligator and snake-infested waters or clambering to the top of an Appalachian mountain in a violent rainstorm, but I stayed with them as they navigated forest trails, swamps, sheer cliff-edges and rutted country roads. They were led by a deep curiosity and unabashed sense of wonder that was compulsive for the reader. I thought of their narrative as offering a master class in how to be in the world, how to be open and really observant of all that life offered. And they had so much fun! Though sometimes exhausted, sometimes in real danger, they delighted in hearing birdsong, catching sight of shy flowers, noticing the varieties of trees, moss and ferns, watching bees and ants, following tracks and peering into burrows and nests; everything was of great interest.

One of their chief delights—and of the reader’s—was that the chosen route and timing of their trip was set to coincide with major migration patterns of birds returning to their northern locations in spring. The many varieties of warblers and sparrows, the robins and shorebirds, hawks and wrens, the great “bands of avian life” winging northward, calling, peeping, singing, silently and with great fanfare sweeping the skies, descending and rising, announcing themselves and the season: each named and described, counted and accounted for. It was thrilling to imagine.

Do we still have massive movements like this? Reading along, we are gifted with the Teales’ shared wealth of experience, knowledge and insight into a world largely lost to us now through over-development, massive freeways, deforestation, dam-building, and land-draining. But, in remnants, perhaps still recognizable and worthy of study—and saving. Their descriptive legacy creates a kind of baseline of what was and a guide to restoration if possible. It’s true they worked and wrote in days before the recognition of climate change changed everything, but what shone through was their excitement for what was there. Instead of being discouraged, I felt lifted up by being in their company. The most unlikely-seeming places were rich with discovery; it may still be so. “Go slow and see more.” Still so very true.