(by Anne Kilgannon) – I don’t want to tell you how many books I’ve ventured, notated, loved and despaired over in my search for this essay topic. Perhaps it’s the season, the government shutdown impasse or just my state of mind. It is my state of mind: no doubt at all; confronting in each book and grappling with the impossibility of the lovingly crafted description of the end of the natural world and all its complicated and cherished living interconnected beings has left me bereft and empty of response. All I can promise is to try again.

(by Anne Kilgannon) – I don’t want to tell you how many books I’ve ventured, notated, loved and despaired over in my search for this essay topic. Perhaps it’s the season, the government shutdown impasse or just my state of mind. It is my state of mind: no doubt at all; confronting in each book and grappling with the impossibility of the lovingly crafted description of the end of the natural world and all its complicated and cherished living interconnected beings has left me bereft and empty of response. All I can promise is to try again.

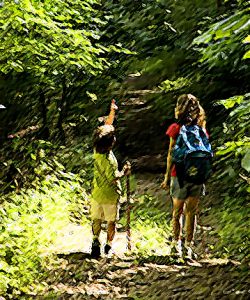

So I started over in a new place, by chance falling upon an essay by Barry Lopez that goes back to the beginning: childhood, his own and then children of his acquaintances, and what he remembers, and then forgot, and now remembers anew with insight for all of us. He writes of an early experience that profoundly shaped him: it came as a confirmation that the world is full of wonder and that he was right to be astounded by that. He speaks of carrying that revelation forward whenever he can with children—and I would say, in all his writing and how he lives his life.

He tells of a time when this truth was masked by “encyclopedic knowledge of the names of plants or the names of birds passing through in a season.” The great lesson was to learn to say less, to allow children to see afresh and without the weight of labels and systems, just for now to let them discover the natural world prompted only by their own curiosity.

“I remember once finding a fragment of a raccoon’s jaw in an alder thicket. I sat down alongside the two children with me and encouraged them to find out who this was—with only the three teeth still intact in a piece of the animal’s maxilla to guide them. The teeth told by their shape and placement what this animal ate. By a kind of visual extrapolation its size became clear. There were other clues, immediately present, which told, with what I could add of climate and terrain, how this animal lived, how its broken jar came to be lying here. Raccoon, they surmised . . . If I had known more about raccoons, finer points of osteology, we might have guessed more: say, whether it was male or female. But what we deduced was all we needed. Hours later, the maxilla, lost behind us in the detritus of the forest floor, continued to effervesce. It was tied faintly to all else we spoke of that afternoon.”

Those children will know raccoons now in a way that will be indelible and transformative. Lopez then acknowledges, “. . . a single fragment of the whole is the most invigorating experience I can share with them. I think most children know that nearly anyone can learn the names of things; the impression made on them at this level is fleeting.” This was food for thought, but Lopez mused further and quietly extended this observation:

“The most moving look I ever saw from a child in the woods was on a mud bar by the footprints of a heron. We were on our knees, making handprints beside the footprints. You could feel the creek vibrating in the silt and sand. The sun beat down heavily on our hair. Our shoes were soaking wet. The look said: I did not know until now that I needed someone much older to confirm this, the feeling I have of life here. I can now grow older, knowing it need never be lost.”

I read that over and over. Yes, children are born open and willing to love the world. It is our job to nurture that flame, confirm and strengthen that inherent tendency—and share our own love and sense of curiosity, to get down in wet mud together in joy and the surprises the world delivers. Let a grin be our language!

I can’t resist giving you Lopez’s exalted final remarks:

“The quickest door to open in the woods for a child is the one that leads to the smallest room, by knowing the name each thing is called. The door that leads to the cathedral is marked by the hesitancy to speak at all, rather to encourage by example a sharpness of the sense. If one speaks it should only be to say, as well as one can, how wonderfully all this fits together, to indicate what a long, fierce peace can derive from this knowledge.”

Reflecting, I feel sure we Black Hill members are on the right track with our program of providing birding backpacks. We are opening doors and windows and removing barriers of accessibility and hesitation to the world of nature. And we are affirming by our attention and encouragement, our own love and willingness to wade into the waters and forests in search of what is hidden there. I am excited to see what fruit will bear from Richard Louv’s community talk on getting children—and everyone else—outside to play. We can’t lose this generation; we have no children to spare.