By Kim Adelson

Many of us are (rightly) concerned with the threat that climate change poses for birds in the future and this is a topic that I frequently write about for this publication. I thought that it would be a nice change of pace to look back and examine how our bird populations here in the Olympia area have changed over time. My original thought was to go back 70-80 years and track changes in our Christmas Bird Count data. The Olympia Christmas Bird Count provides a consistent, one-day snap picture of our winter birds. It turned out to be unfeasible to examine so many years, however, since the number of counters/counting groups was very small in the 1950s and 1960s, and therefore the bird numbers from those years are not comparable to later counts since fewer groups cover a smaller, less representative geographical area. Participant numbers increased in the 1970s, but only after an 8 year-gap in which no counts were conducted. Therefore, I included data from 1978 to 2019. There are only 3 missing years in that time period, and so I scrutinized data from 39 years of Olympia-area Christmas Bird Counts.

This is a huge undertaking, and so I am going to discuss only a small number of bird species in this (and future) articles. I am beginning with the Columbidae, or pigeons and doves. Why? The number of local species is small and manageable and because I am very fond of some of them. We currently have four species of pigeons/dove in our immediate area: rock pigeons (city pigeons), mourning dove, Eurasian-collared dove, and band-tailed pigeons. Doves are easily observed, almost exclusively vegetarian, and are among the few birds that can drink by sucking water as opposed to lapping it up. They are unique in that they produce “crop milk” to feed their hatchlings. Personally, I find the cooing sounds that they make quite pleasant.

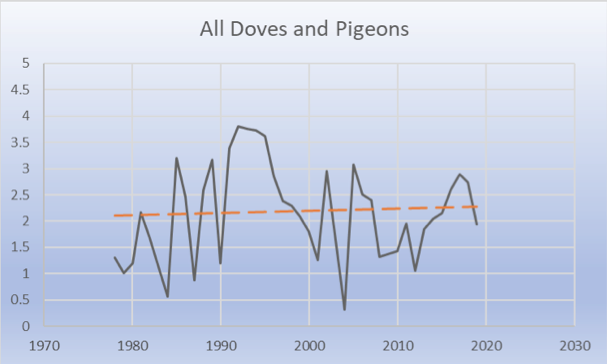

So, how are our local pigeons/doves faring? Overall, at least in the winter, it appears that our Columbidae population is stable. (All assertions are based upon the regression analyses that I ran; I will not bore you with the R and p values.) Although the red trend line appears to rise slightly, there is too much variability in the data for such a small increase to mean anything. I am always happy to see that birds are holding their own and not decreasing in number!

Note: the numbers on the Y axis (up the left side) of this and all following graphs reflect the adjusted number of birds seen on the Bird Count. The raw numbers of observed birds are standardized by the numbers of groups that were out observing and the amount of hours they spent looking. For example, if 5 groups were out for 10 hours each, that is fifty “group hours”. Say that they collectively saw 100 doves/pigeons in that time: 100/50= 2 standardized group hours. This converted statistic is a more accurate reflection of bird density than total birds counted due to yearly differences in number of count participants.

This does not necessarily mean, though, that all four species of local pigeons/doves have stable populations – and in fact they do not.

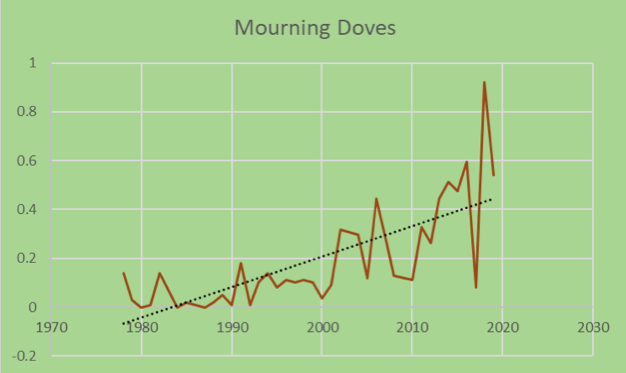

Mourning Dove

Nationally, the mourning dove population has declined by about 15% since 1966. This may be due to hunting – they are the most commonly taken game bird in the U.S. – or habitat loss. Our local birds are faring better:

As you can see by the sharp slope of the trend line, locally mourning doves are becoming more common, at least in December.

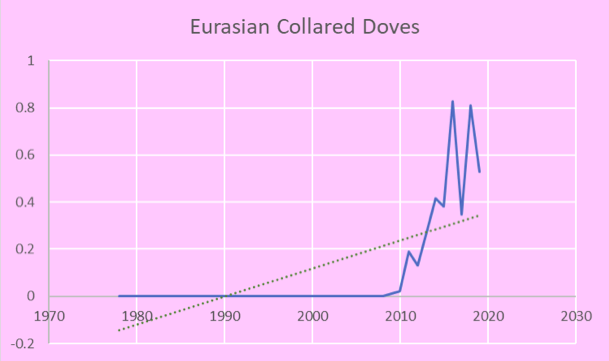

Eurasian Collared-Dove

Another dove whose numbers are increasing, in their case nationally as well as locally, is the Eurasian Collared-Dove. These birds didn’t weren’t even recorded here until 2009, and now most of us see and hear them with good frequency. As many of you know, these birds were released in the Bahamas in the mid-1970s and have quickly spread north and west across the United States.

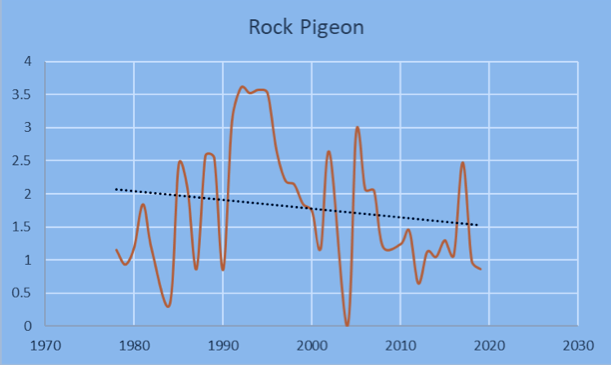

Rock Pigeons

These birds are the ubiquitous city pigeons that are found in cities all over the world. They obviously well-tolerate the presence of humans. Our local population has remained stable for the last forty years. The trend line appears to dip lower with time, but the variability of the counts is too great for the results to be statistically significant.

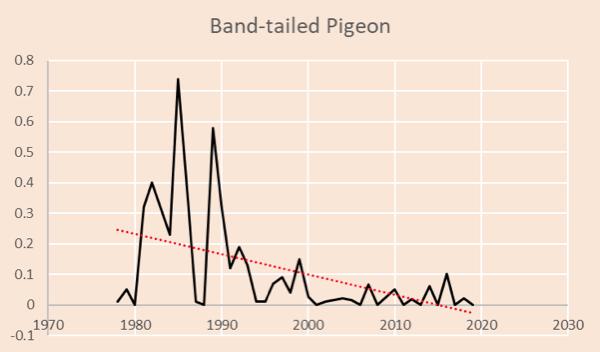

Band-tailed Pigeons

Well, if our total winter dove/pigeon population is holding even while two species are decreasing and one is remaining sable, it stands to reason that the remaining species must be declining. And, unfortunately this is true – and not only here, but nationally as well. Cornell University estimates that there has been more than a 60% reduction in the number of band-tailed pigeons in the U.S since the 1960s, probably from a combination of hunting and urbanization.

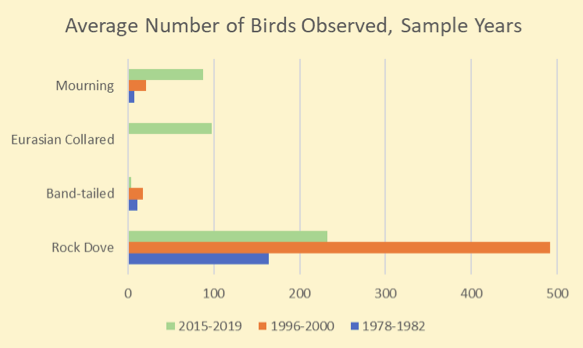

Finally, I wanted to give you a sense as to how relatively common each of these birds are. To begin with the big picture, doves/pigeons make up slightly less than 1% of the birds observed since 1978 in Christmas bird count (slightly more than 1% if you remove shore and water birds). I assume that they seem more numerous because of their noisy nature and tendency to perch in readily-seen locations. As the graph below shows, rock doves are and have been more common that the other dove species in the past forty years. We now have roughly equal numbers of mourning and Eurasian-collared doves, but that is a new phenomenon. Band-tailed pigeons have consistently been the most rare.

Anyway, I hope you found this information interesting. There are many more bird families to come!